Exercise 1: What is an advocacy planning cycle?

Aim: To consider the different stages in an advocacy planning cycle and in developing an advocacy strategy.

Step 1: Plenary presentation

Before you start advocating, it is really important to have a clear strategy in mind.

Steps 2 and 3: In groups, then plenary Put various elements in an advocacy planning cycle and in developing an advocacy strategy on cards. Give each group a set. See page 2.

- Ask participants to put them in an order they think is appropriate, identifying the reasons for this choice. Afterwards you can discuss why they chose this order.

- Feedback: each group feeds back; note on flip chart ‘Issues Arising’.

Exercise 2: Identifying the problem and finding a solution

Aim: Participants to use problem and solution trees to identify the root causes of the issue they want to address and develop goals and objectives to tackle it.

- In plenary, demonstrate how to do problem and solution trees and why they’re a useful tool for developing goals and objectives.

- Divide participants into small groups (maximum of four in each group) and ask them to do their own trees based on an issue they are concerned with.

The facilitator explains that this model is useful for:

- breaking down broader issues

- identifying the root problem and articulating the solutions

- exploring the range of advocacy areas where participants may choose to intervene to bring about positive change.

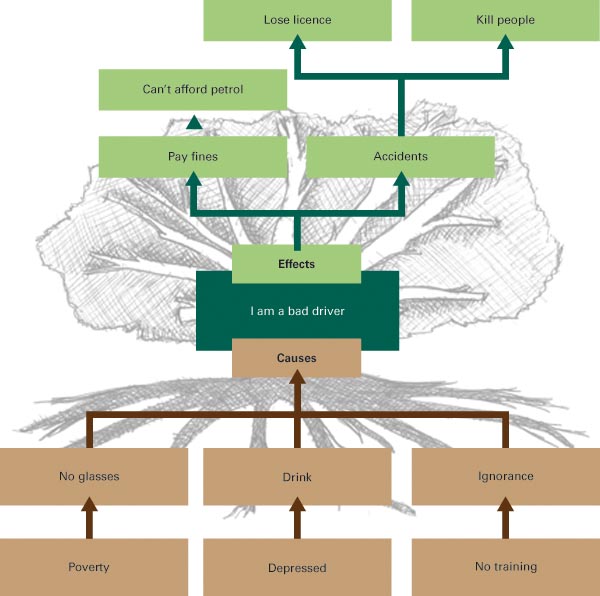

General example of a problem tree:

Problem tree – how to use this tool

Step 1: Draw a tree trunk on a large sheet of flip chart paper. The trunk represents the problem or situation you are investigating.

Step 2: Add roots. They represent the causes of the problem or situation. Some roots are closer to the surface: these are the more obvious factors that contribute to the problem. But what causes these factors? The deeper you go, the more causes you uncover that help to contribute to the problem or situation.

Step 3: Draw the branches. These represent the effects of the problem. Some branches grow directly from the trunk: these are the problem’s more immediate effects. But each branch may sprout many more branches, showing how the problem may contribute to a range of indirect and longer-term effects.

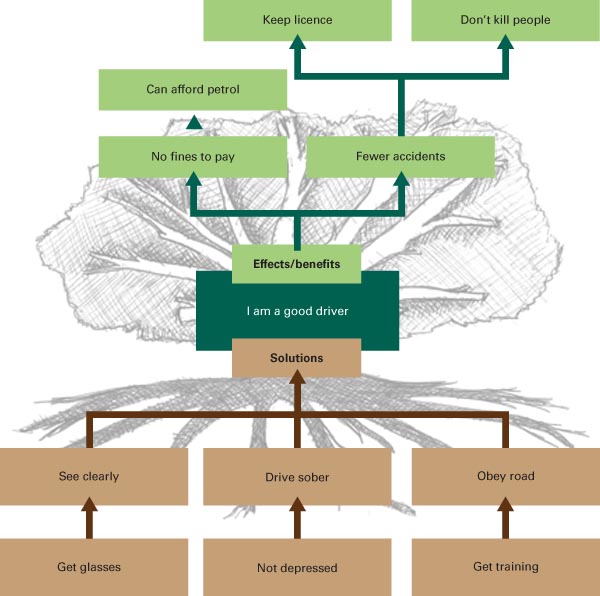

General example of a solution tree:

Solution tree – how to use this tool

The solution tree turns the negatives in your problem tree into positives, which can in turn be developed into goals and objectives.

Step 1: Draw a tree trunk on a large sheet of flip chart paper. The trunk represents what you would like a certain situation to be like in the future.

Step 2: Add roots. They represent possible solutions or methods to bring about the desired future situation. The solutions should relate to the main causes of the problem as indicated in the roots of your problem tree. The roots that are closer to the surface are those that would contribute most directly to improving the situation. The solutions may also reinforce

each other.

Step 3: Draw the branches. These represent the effects of the improved situation. Some branches grow directly from the trunk: these are the more immediate effects. The longer branches are used to represent the longer-term effects of the improved situation.

Exercise 3: Power analysis

Aim: Participants to develop a power map on their tax issue. They have a clear analysis of the principal actors who can influence or make decisions about the goal and they understand the networks and relationships between people and key institutions.

Step 1: In groups, participants draw a power map (see the power mapping tool on page 8 for an example).

Draw and label a box or circle in the middle of a flip chart sheet to represent the person or institution with the most power to bring about change on your issue. Then work outwards so that the circles/ boxes near the centre of the sheet have the most power to change the policy and the circles/boxes on the edges of the sheet are those with the least power. Participants discuss their choices as they develop the power map.

Step 2: Still in groups, participants add arrows going from one box/circle to another to demonstrate who has power over other bodies and individuals.

Step 3: You can further discuss the choices that participants made and the reasons for them in plenary.

Exercise 4: Identifying and mapping key stakeholders

Aim: Participants to identify a broad range of actors with a stake in a given tax issue (to complement the analysis of who has power over the issue in Exercise 3). Participants will analyse four main categories of stakeholders: targets; allies; opponents; and beneficiaries.

Step 1: The facilitator reminds the group that most tax issues have multiple stakeholders. Some will be targets of the advocacy (because they have the power to bring about the change being sought – as identified in the power map exercise). Some will be allies, others opponents. It’s also important to clarify who will be the beneficiaries of the changes sought.

NB: There may be some overlap between different stakeholders – that is, the targets of the advocacy may also be opponents or allies.

Step 2: Divide participants into small groups of four or five. Each group will need to decide what tax issue they will focus on (ideally the same issue they used in the power map exercise).

Step 3: Give each small group four sheets of flip chart paper, each one headed with a different stakeholder category as follows: Targets, Allies, Opponents, Beneficiaries.

Step 4: In these small groups, ask participants to:

- make lists of different stakeholders with a stake in their issue, using the four sheets of flip chart paper (that is, lists of targets, allies, opponents and beneficiaries). The ‘Who’s Who’ of tax stakeholders on pages 9–11 will provide some ideas about relevant stakeholders, but there may also be other stakeholders relevant to your context or tax issue.

Step 5: Introduce the stakeholder analysis table (see the tool on page 12). Take each stakeholder the group has identified and ask the following questions:

- What interest do they have in this issue? Rank: Low, medium, high.

- To what extent do they agree with you on the issue? Rank: Low, medium, high.

- How important is this issue for them? Rank: Low, medium, high.

- How much influence do they have over the issue? Rank: Low, medium, high.

Step 6: If there’s time, ask each group to start discussing what approach they might take with each of these stakeholders.

NB: How we influence different stakeholders will be explored in more detail in Chapter 4: Getting active on tax.

The following are questions to pose when discussing different approaches to stakeholders (the facilitator could display these questions on a PowerPoint slide or on a flip chart for all groups to see):

- u Are our opponents also our main advocacy targets? If so, what approach is most likely to change their position?

- u If our opponents are not our main advocacy targets and don’t have much power over the issue, can we ignore them? Or do we need to neutralise their opposition?

- u Are any of our allies also our main advocacy targets? If so, how can we use these powerful

- allies to maximum advantage?

- u How closely should we seek to work with our allies? To what extent do they agree with us? What is the common ground?

- u Should we seek to involve our beneficiaries in the advocacy work? If so, how?

Step 7: In plenary, ask each small group to do a brief report back on their stakeholder analyses.

If short of time, ask each group to present their analysis of one of the stakeholder categories.

Exercise 5: Smartening up your objectives

Aim: Participants to learn to develop SMART objectives for their advocacy strategy.

Step 1: In plenary, the facilitator provides three or four examples of objectives that do not meet SMART criteria and asks participants to discuss in pairs why they are not SMART.

Step 2: In groups:

Split into issue groups (for example, different issue groups on tax could be: how to make our national tax system more transparent; how to make our national tax system more equitable; how to persuade our government to stop giving overly generous tax breaks to investors). Groups to return to problems and solutions drawn from the problem and solution tree exercise to help them develop two to four SMART objectives.

Step 3: Groups feedback in plenary:

Each issue group feeds back on one objective in plenary and the facilitator/participants check whetherthey are SMART.

Examples of objectives that are not SMART:

- XX development NGO to land a rocket on the moon in one year (not achievable or realistic, but it is timebound)

- To eradicate world poverty (not specific or timebound)

- To tackle HIV/AIDS in Sudan within a decade (not specific and therefore not measurable)

Chapter 2: How to develop your tax advocacy strategy

- the advocacy cycle and its six elements, including:

- identifying the problem and its root causes and finding a solution

- assessing your external context, including identifying your key tax stakeholders and who has the power to help you achieve the change you seek

- setting your tax goals, objectives and indicators

- developing your key messages on tax and tailoring them to your target audience

- deciding on your advocacy approach – will you adopt an inside or outside strategy to your tax justice issue?

- planning your monitoring and evaluation.

Chapter 3 gives guidance about how to carry out research on tax, in particular:

- guidance on core research methods and tools to help you conduct advocacy-focused research on:

- government tax systems

- the tax contribution of companies.